Data: 10/02/2022

Evento: Antonino Calcagnadoro’s Divisionism: a rediscovered collection

This group of paintings provides an insight into the work of a painter who is still awaiting rediscovery and full understanding by critics: Antonino Calcagnadoro (Rieti 1876 – Rome 1935). A member of the generation of Roman Secession painters, whose art he was in some ways akin to, Calcagnadoro preferred to carve out a secluded role for himself in the artistic panorama of the capital in the early 20th century, but not for this reason a marginal one. Son of art (his father Cesare Calcagnadoro was an appreciated decorator), the artist from Rieti worked for a long time in the field of decorative art, achieving his most important successes with monumental paintings for architectural environments (Rieti, Sala Consiliare; Ligurian Pavilion at the Ethnographic Exhibition of 1911; Salone dei Ministri in the Palace of the Ministry of Education). The fame he achieved through this type of activity led him to obtain first a chair at the “Scuola preparatoria alle arti ornamentali” (preparatory school for the ornamental arts) of the municipality of Rome, then at the Institute of Fine Arts, where he was in close contact with Adolfo De Carolis.

In parallel with his work as a decorator, Calcagnadoro devoted himself with enthusiasm and greater creative freedom to easel painting, constantly presenting the results of his research at national exhibitions. After his initial attempts to explore the themes of antiquity, in the early years of the 20th century the painter turned to the ‘humanitarian socialism’ of Duilio Cambellotti, Giacomo Balla, Giovanni Prini and Domenico Baccarini. His socially themed works convinced critics and institutions alike, as evidenced by the gold medal he was awarded for his painting The Unemployed, a dramatic painting of denunciation exhibited at the Florence Promotrice in 1904.

Perhaps in deliberate opposition to the rhetorical language of architectural friezes and decorations, Calcagnadoro presented himself as a painter of reality in the paintings exhibited at the Promotrice: a realist approach characterises all his paintings, including views, portraits and genre scenes, even when they are cloaked in Symbolist suggestions. This is the case with the paintings presented here, all of which were made during his call to arms between 1916 and 1917. In each of them the painter from Rieti uses the Divisionist technique, which was at the centre of a rediscovery by Roman painters at the time. Varying in subject matter between intimate domestic scenes, urban views and animal subjects, these works offer an eloquent insight into a phase of Calcagnadoro’s research that is otherwise little known.

Calcagnadoro’s use of the divided touch is a departure from the pointillism or tessellated touch of his better-known Roman colleagues, such as Innocenti, Lionne and Noci. His brushstroke is filamentous, with a strongly draughty character – the influence of illustration, which he himself worked on for magazines and newspapers, is not unfamiliar – in which the memory of late nineteenth-century northern Divisionism emerges.

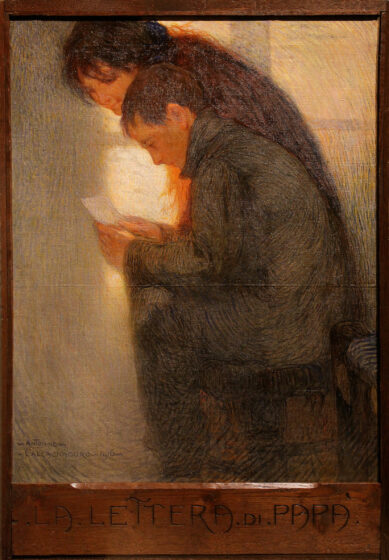

Pellizza, Segantini and Previati are clearly Calcagnadoro’s reference models in this group of works. The melancholy scene of the mother with children, in which the profiles of the figures emerge from a dense weave of minute filamentous marks in brown tones, is derived from Previati. The result of a more original combination of references is Dad’s Letter, a painting with a frame and engraved inscription made by the artist, which completes the painting and enhances its narrative values. Here, the Divisionist brushstrokes render a warm twilight light, filtered through a window, which invests the figures in a play of symbolic references. The theme of children reading a letter sent by their father, who was defending his country at the front, is a topos of international painting during the dramatic years of the First World War, in which Calcagnadoro was personally involved. However, the artist seems to have been inspired by a work from before the war: the central panel of Giacomo Balla’s famous 1910 triptych Affections, now in the collections of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome. A highly introspective work, Dad’s Letter was exhibited in 1917 at the great national exhibition of painting, sculpture and black and white “Visions of War” at the Circolo Artistico in Rome. Among others, Giovanni Prini, Cipriano Efisio Oppo, Francesco Trombadori, Giovanni Battista Crema and Giuseppe Mentessi also exhibited. The critic Arturo Lancellotti, in a long review for the magazine “Emporium”, praised the work for its “good quality of drawing and colour” (A. Lancellotti, Cronachetta artistica: la guerra vista dagli artisti italiani, in “Emporium”, 1917, vol. XLVI, p. 276).

The artist followed up this work with a similar painting in 1918: Daddy Doesn’t Come Back, exhibited the day after the end of the war at the exhibition Children and Flowers, organised by the Società Amatori e Cultori di Belle Arti in Rome for the benefit of war orphans. The child in the painting is once again seated, but this time facing frontally, asleep in the vain expectation of his father who is destined never to return. Purchased there by a collector from Turin, the work was replicated by Calcagnadoro, with minor variations, in a painting of 1923 now in the Museo Civico in Rieti.

Manuel Carrera